Rare disease day 2022

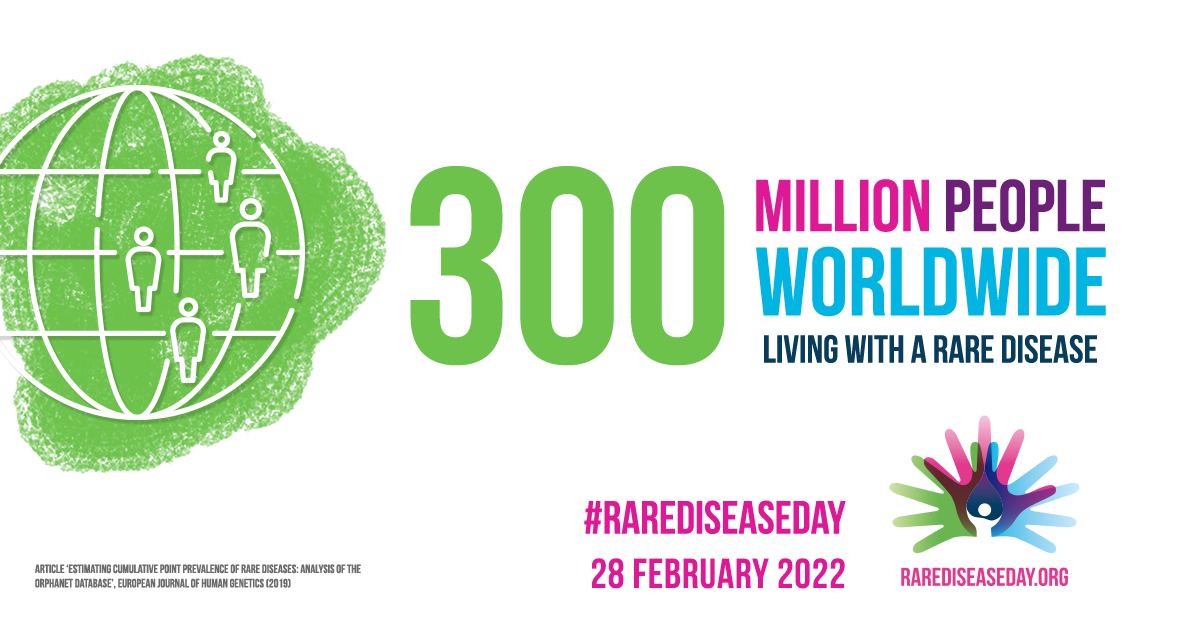

Today, Monday 28th February 2022, is rare disease day: a globally-coordinated and patient-led movement to raise awareness of the 300 million people across the world living with a rare disease, as well as their families and carers. Find out more here.

To mark the day we decided to share what motivates each of us to study the genetics of rare disease, and also a few of our favourite rare disease facts.

Nechama (DPhil student)

“Through volunteering for Jnetics (a genetic screening charity) and other genetic counseling work experiences I witnessed how not knowing the cause of a patient's disease is devastating. I also saw firsthand how difficult it can be for patients with rare diseases to not know what is “normal” for their disease course as there are too few patients to infer meaningful predictions. The challenges faced by the rare disease community and my passion for using technology to improve patients’ lives inspires me to contribute to this field.”

You may think “how much effort and resources should we spend on rare disease research if they are by definition, rare?”.

When we combine all people with rare diseases and look at them as one group, this amounts to a significant proportion of the population (~1 in every 17 people).

Alex (postdoc)

“Academically, I came into rare disease analysis via what would be considered to be a quite unusual route, having started with a BSc in Archaeology. Towards the end of my undergraduate degree I began to develop an interest in ancient DNA analysis, and in particular using bioinformatics to better tease out the signals in genetic data. I could say that it was this interest that fed into my MSc and Later PhD in that field, and that would in part be true, but it wasn’t the catalyst.

On the first day of the final year of my undergraduate degree I was diagnosed with cancer. This was the third different cancer diagnosis I had received over a 15 year period, and I was not yet 30. By the third diagnosis I also had a significant family history of cancers, so my oncologist at the time raised the possibility of genetic testing. Up to this point the prospect of there being a genetic basis for whatever was leading to my illness hadn’t really occurred to me, but from the moment they drew the first vial of blood to run the initial tests I found I had a hunger to learn everything I possibly could about genetics, and more specifically, why certain variants can cause disease, whilst others do not.

Unfortunately, 10 years on from those initial tests, if there is a genetic basis for my disease we have not yet found it. Given the nature of rare disease it is currently not uncommon for patients to face very long journeys when seeking a genetic diagnosis, I remain hopeful that mine will happen one day. In the meantime, I have chosen to make the best use of my experiences as a rare disease patient, and bioinformatician to attempt to help others put an end to their diagnostic odysseys.”

~80% of rare disease is thought to be genetic in origin, but for over half of rare disease patients the genetic cause of their disease is currently unknown.

Maria (postdoc)

”I have been exposed to rare diseases from another perspective since I was young, as I have a family member with a rare disease. From a more lived experience to genetics, that was a small step, as since childhood I have been always very curious and later on fascinated by biology and biochemistry, wanting to understand how little/big changes in our genetics lead to so many different outcomes (phenotypes). Additionally, the difficulties of unraveling the processes behind rare diseases makes the topic even more intriguing to me.”

A disease is defined as ‘rare’ when it affects fewer than 1 in 2000 individuals. There are more than 6000 such rare diseases.

Elston (research assistant)

“Every one of us is unique. And while a person's genome could be stored on a single DVD, we have barely managed to reliably figure out what different people's genomes do. My interest has always been to tease out what about the genome makes us different from each other, such as why do drugs work on some people but not others? Or why some people are more at risk of one disease than others? Because these differences matter, from the clinician making the diagnosis - to the patient themselves.

I like to think that better understanding rare disease is the only sensible strategy if we ever wish to dream of a future with personalised medicine. Only when we have built a reliable framework for diagnosing and treating rare diseases do we have a shot at making biomedical science open and accessible for all.”

Nicky (group leader)

“I was first fascinated by genetics through trying to understand why my cousin Jonathan had Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), but neither of his brothers nor anyone else in the family did. At school I had always wanted to be a doctor to make a difference to the lives of patients, like Jonathan, but I changed my mind just as I was applying to university and instead studied Natural Sciences (mainly Chemistry, Physics and Maths). I remember being in a first year lecture taught by Dr David Summers and deciding that genetics was what I wanted to study in the final year of my degree. I feel that where I am now - conducting research on rare diseases - satisfies both my desire to ‘make a difference’ and my fascination with science and in particular genetics. I get incredibly excited by identifying new diagnoses for individual patients and I believe that is in part due to knowing first hand the difference that can make to a family.”

DMD almost exclusively affects males as it is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene which is on the X chromosome. Around 2/3rds of individuals with DMD inherit the mutation from their mothers who carry the mutation but are not affected.

To end, we would like to say a huge thank you to all of the individuals, both with and without rare disease, who contribute to the datasets that enable us to do what we love, which is scientific research. When we work together, we can make a big difference.